The Dispossession of Orang Asli Customary Land: A Review of the Malaysian Government

by Joey Chee, The Leys School

1.0 INTRODUCTION

1.1The Orang Asli Hardship

The Orang Asli, which translates directly to “Original People” in English, are the indigenous people of Peninsular Malaysia. They make up 198,000 people or 0.7% of the population of the peninsular1. Nicholas, “A Brief Introduction”, Center for Orang Asli Concerns (2012) and are the ethnic minority of Malaysia – a separate identity from the natives of Sabah and Sarawak. While their status as the first inhabitants of Malaysia is rarely disputed, this does not necessarily translate into the recognition of their rights as indigenous people of the land2Y. F. Chung, The Orang Asli Of Malaysia: Poverty, Sustainability and Capability Approach (2010). A key issue that they face is the dispossession of customary land. As the ownership of customary land is subjected to the goodwill of Malaysian state governments3Aboriginal Peoples Act 1954 6(1), p.14, the Orang Asli are left vulnerable to the non-gazetting and degazetting of their lands. As of 2012, approximately 12% of the 869 Orang Asli settlements have only been gazetted 4C. Nicholas, “A Brief Introduction”, COAC (2012).. The majority of Orang Asli villages have long been susceptible to acquisition for private and state purposes – demonstrating the negligence towards the loss of a culture that has existed for generations, as well as the livelihood of entire communities.

1.2 Research Motivation

A term that has been highly contested in Malaysia is the ambiguous “Bumiputera”, translating into “sons of the soil”. This word acts as a “catch all” term that collectivizes the Malays, Orang Asli and natives of Sabah and Sarawak in Federal legislations. What is important to note, is the absence of this term in the Federal Constitution. This means that despite the existence of policies that serve to grant the Bumiputera exclusive economic and social benefits – which exist as quotas in the education and corporate spheres of Malaysia – there is no absolute definition for it. These privileges line up with the “special position” of the stakeholders of Article 153 of the Constitution, of which the Orang Asli are explicitly not a part of.

153(1) It shall be the responsibility of the Yang di-Pertuan Agong to safeguard the special position of the Malays and natives of any of the States of Sabah and Sarawak and the legitimate interests of other communities in accordance with the provisions of this Article.

Ultimately, this creates room for the term “Bumiputera” to be interpreted as only encapsulating the Malays and natives of Sabah and Sarawak. In collectivizing three entirely different ethnic groups both in terms of their needs and in numbers 5The Malays are the ethnic majority in Malaysia and live predominantly in urbanized areas, while Orang Asli settlements often lack access to the same quality of basic amenities – if at all – in comparison to the rest of Malaysia., policies that favor the Bumiputera have led to a false sense of reality regarding the support that the Orang Asli are actually receiving. The ill-defined relationship between Bumiputera benefits and the Orang Asli has led to my inquiry as to who the Orang Asli are. As such, this led me to pursue a research project on the dispossession of Orang Asli customary land.

1.3 Research Hypothesis

This paper explores the issues regarding the dispossession of Orang Asli customary land, and its consequences on the Orang Asli community. The aim of this paper is to explore the following questions:

- What is the reason for the dispossession of Orang Asli customary land?

- How does the government play a role in this issue?

- What is the possibility and the feasibility of change occurring in the status quo?

2.0 METHODOLOGY AND PROCESS

2.1 Literature Review

Upon understanding the dispossession of Orang Asli land and the issues revolving around it, secondary sources were used; taking the form of academic journals, research papers and books. The same sources were used in formulating my arguments, which were founded on research that key contributors and experts in the study of the Orang Asli have produced. These are individuals who have been researching and working with the Orang Asli in fighting for their rights, protection and representation in Malaysia. This was complemented by court cases and interviews that demonstrate the stance of the Malaysian government in regards to the dispossession of Orang Asli land.

2.2 Interviews

My interview with Dr. Colin Nicholas, whose profession and reputation in fighting for the cause of the Orang Asli is highly regarded, was an insightful primary source for this project. Nicholas is the founder of the Center for Orang Asli Concerns (COAC), which was “established in 1989 to advance the cause of the Orang Asli – whether via the greater dissemination of Orang Asli news and views, assisting in court cases involving Orang Asli rights, or in developing arguments for lobbying and advocacy work”6C. Nicholas, “A Brief Introduction”, COAC (2012). Our interview was conducted during the early stages of the project, and his experience working with the government and legal authorities provided ample insights as to the relationship between the dispossession of Orang Asli customary land and these authorities.

3.0 IDENTIFYING THE ORANG ASLI

3.1 Who are the Orang Asli?

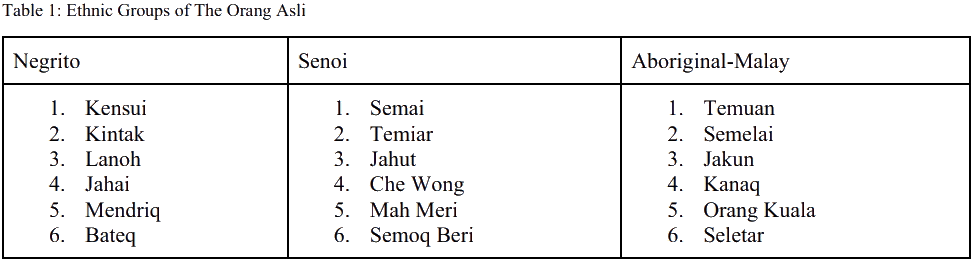

The Orang Asli are, first and foremost, not a homogeneous group. They are divided into three main tribal groups for administrative purposes: Negrito (Semang), Senoi and Aboriginal-Malay. Within these groups are 18 ethnic groups, with each one having its own unique way of living, culture and language, as found in Table 1. Their distinct identities are derived from their geographical space, which they have retained due to their relative isolation7T. Marson & F. Masami & N. Ismail, Orang Asli in Peninsular Malaysia: Population, Spatial Distribution and Socio-Economic Condition (2013), p.81 from the rest of Peninsular Malaysia. These identities consist of their knowledge systems and beliefs, from which their livelihoods stem from. The manner in which the Orang Asli identify with their geographical space dates back to before the ethnic category of ‘Orang Asli’ was created. They did not allow ethnic markers to differentiate themselves, and only adopted the term ‘Orang Asli’ during the Malayan Emergency.

3.2 Culture and Connection to Customary Lands

The United Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) provides the international recognition of indigenous relationships to land in Article 25. The annex of the UNDRIP provides pertinent recognition of the “urgent need to respect and promote the inherent rights of indigenous peoples which derive from their political, economic and social structures and from their cultures, spiritual traditions, histories and philosophies, especially their rights to their lands, territories and resources”. It is important to recognize that “The Orang Asli, like indigenous communities elsewhere, are communities linked to the land, not just land per se, but a particular piece of land, a particular ecological niche, or geographical space. Other people are interested in land as a commodity, but land for indigenous people is their identity, what makes them who they are.8C. Nicholas, The end of the world for the Orang Asli (SUHAKAM).” As Nicholas explained, the formation of the identity of the Orang Asli is intertwined with their relationship to customary land – which is also used for, but not limited to, rituals and burials. Indigenous customary land acts as an emblem that bridges the history of their ancestors and the future of their descendants. In the same way that global cultures are respected by keeping them alive, there exists an obligation to not only recognize but to actively protect Orang Asli culture by protecting their customary lands.

Customary lands also play a central part in the economic and subsistence livelihoods of the Orang Asli. While they have always participated in both trade and the subsistence economy, both means of survival are rooted in their use of customary land. Each ethnic group has a unique understanding of the environment around them that has been passed down for generations through oral tradition 9Interview with C. Nicholas., and has allowed them to maintain their livelihoods in the sustainable way that they have done for centuries. The variations between each geographical location – be it one that is minute or consequential – plays a significant role in the differences between the knowledge and use of land between each ethnic group. In this sense, it is insufficient for the Malaysian Government to provide an alternative piece of land in acquisition of Orang Asli customary land – as seen in 1993 when the state government of Johor Bahru directed the relocation of the Orang Asli Seletar from Stulang Laut to Kuala Masai in acquisition of their land10This issue was brought to both the High Court of Johor Bahru and the High Court of Appeal (Putrajaya), in which both courts ruled the cases in the Orang Asli Seletar’s favor. This granted them entitlement to compensation from the defendants (which included the state government of Johor Bahru).. Hamimah Hamzah quoted Rameli Dollah in his journal, ‘The Orang Asli land: Issues and Challenges’ when he said that “Land is the lifeline of Orang Asli … To chase Orang Asli from their land means to destroy their identity and life …”. The inseparable relationship between the Orang Asli and customary land is one that cannot be disputed in protecting the rights of the Orang Asli as a whole.

3.3 Shut Out: The Problem of Marginalization

The mischaracterization of the Orang Asli that currently exists dates back to the colonial era of Malaysia. The misconceptions of the Orang Asli being nomadic, uneducated and anti-development continue to persist even today. Upon depicting the Orang Asli as impotent, it validates the intrusive and authoritative nature 11APA 1954 (16) allows for the government to appoint hereditary headmen, replacing traditionally appointed leaders.in which the government has attempted to assimilate the Orang Asli into the rest of Malaysian society. These misconceptions remain detrimental in pursuing the Orang Asli’s rights to autonomy and to customary land, as Malaysians remain either silent or unaware of the manner in which they have been disillusioned. As mentioned in Section 1.2, this gives birth to the false sense of reality in regards to the help that the Orang Asli are actually receiving, further marginalizing them. This manifests in not only the lack of protection of customary lands, but also in the subpar quality and provision of basic amenities such as electricity, water supplies and sanitary facilities, as well as education that is received from the government12Y. F. Chung, The Orang Asli Of Malaysia: Poverty, Sustainability and Capability Approach (2010), p.27..

Additionally, it is important to recognize the significance of politics in the marginalization of the Orang Asli. As an ethnic group that makes up an almost insignificant percentage of the Malaysian population, they have close to no political stake and thus there is no pressure for changes in policies nor Federal statutes. This can be seen as the protection of Orang Asli customary lands failed to be a priority in both Barisan Nasional and Pakatan Harapan governments. Marginalization will always be ingrained into an echo chamber which continues to perpetuate false stereotypes of the Orang Asli; and is especially so when it is governed by a body that is slow to represent or act upon the interests of these individuals.

4.0 THE DISPOSSESSION OF ORANG ASLI CUSTOMARY LAND

4.1 Overview: The Issue

The dispossession of Orang Asli customary land is rooted in the insufficient protection of the Aboriginal People’s Act 1954 (APA). This grants state authorities disproportionate power over customary lands by putting the Orang Asli into the straitjacket of being tenants-at-will. Alongside that, the Torrens title system, which is defined below, that governs the ownership of land in Malaysia acts as an additional barrier to the Orang Asli accessing autonomous land rights. As to the issue of compensation, the current system of compensation that the Orang Asli receive falls short in complying with the Declaration of Indigenous Organizations of the United Nations13Z. Z. Z. Abidin & S. T. Wee, Issues of Customary Land for Orang Asli in Malaysia (2013), p.2. All in all, it is evident that the laws that are in place are inadequate in protecting the Orang Asli’s rights to land ownership and/or fair compensation.

4.2 Ownership of Customary Lands

Land ownership in Malaysia is governed by the National Land Code 1965 (NLC), Federal Constitution (FC) and Land Acquisition Act 1960 (LAA). The Torrens title system is established in the NLC, purposed to provide conclusive evidence of the registration and/or transfer of land. This is maintained by the government and guarantees an indefeasible title to individuals in the register. Under the Torrens title system, there are three ways to own land: dealings, inheritance or alienation; all of which is done through the registration of land titles. This implies that the acquisition and/or encroachment of any land will always involve the government.

However, it is important to note that the ownership or Orang Asli customary land falls outside of the NLC, as seen in section 4(2)(a):

4(2)(a)Except in so far as it is expressly provided to the contrary, nothing in this Act shall affect the provisions of any law for the time being in force relating to customary tenure; and, in the absence of express provision to the contrary, if any provision of this Act is inconsistent with any provision of any such law, the latter provision shall prevail, and the former provision shall, to the extent of the inconsistency, be void.

Rather than being granted ownership over their lands, the Orang Asli rely on the state to protect their territories through a gazette14An official publication of public notices issued by the government.. The gazetting of Orang Asli reserves is imperative to recognizing their rights over these lands, which is realized through public recognition. This plays a significant role in establishing the Orang Asli’s rights in instances where their land is encroached upon or acquired for both private and state purposes. This responsibility falls onto the State Authority, as stipulated in the APA:

7(1) The State Authority may, by notification in the Gazette, declare any area exclusively inhabited by aborigines to be an aboriginal reserve.

It is important to note that the word “may” implies that the State Authority is not bound to an absolute obligation to protect these customary lands. Article 8(2) of the APA reiterates this, stating that the rights of occupancy “shall be deemed not to confer on any person any better title than that of a tenant at will.” This means that the rights of the Orang Asli over their customary lands are subjected to the goodwill of the state; remaining problematic as it suggests that the protection of their livelihoods is only important insofar as the state decides that it is.

Additionally, there is a distinction to be made regarding the difference in authority that the government and the state possess over Orang Asli matters15The government refers to the ultimate political authority in Malaysia, while the state refers to the political party that rules their respective state.. This distinction is found in the Ninth Schedule of the FC, which includes “Welfare of the aborigines” in Section 16 of the Federal List. While the federal government is granted an overarching authority, the APA specifically designates the issue of land rights over to the state, causing a conflict in power. This also suggests that the intentions of the federal government become obsolete, as the extent to which customary lands are recognized is subjected to the prerogative of the state. In Kedah, the term “tanah adat”16The Malay translation for “customary land”. is not recognized under the state constitution – and thus neither are the Orang Asli’s rights to customary land. This position was maintained by Kedah’s Menteri Besar Dato Seri Ahmad Faizal Azumu in 2019: “As far as I know as a Menteri Besar and a Perakian, we don’t have ancestor land for Orang Asli here… this is very clear.”17Malay Mail, “No such thing as Orang Asli ancestor land in the state, Perak MB told NGOs” https://www.malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2019/07/29/no-such-thing-as-orang-asli-ancestor-land-in-the-state-perak-mb-told-ngos/1775783. The state’s ability to use its extensive powers as a means of disregarding the existence of entire generations of communities proves itself to be a barrier to establishing the ownership of customary lands; leaving the Orang Asli all the more vulnerable.

4.3 Non-gazetting and Degazetting of Customary Lands

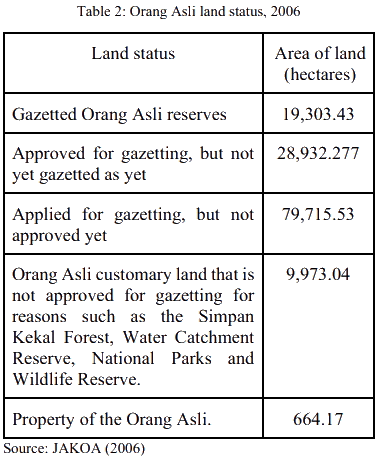

The non-gazetting of customary lands is one of the root causes of the dispossession of Orang Asli lands. As explained in Section 4.2, the state is not in an obligation to gazette these lands according to the APA. A significant number of villages have not been gazetted despite their application; and in the instance that applications have been approved of, many are yet to be officially gazetted. The Department of Orang Asli Development (Jabatan Kemajuan Orang Asli, JAKOA)18Z. Z. Z. Abidin & S. T. Wee, Issues of Customary Land for Orang Asli in Malaysia (2013), p.3. divides the 138,861.43 hectares of Orang Asli customary land in 2006 as seen in Table 2 below:

The issue with the non-obligatory nature of sections 6 and 7 of the APA manifests in the fact that only 13.9% of all Orang Asli customary lands were gazetted as of 2006. In 1965, Kampung Gerachi – one of the two villages involved in the relocation of Orang Asli settlements due to the construction of the Sungai Selangor Dam in Kuala Kubu Bharu – had 404.04 hectares of land approved for gazetting. Up until today, these lands are yet to be gazetted. It has to be recognized that this is not an isolated instance – this area of land only makes up 0.01% of the 20.8% of all customary lands in 2006 that have been approved for, but are not yet gazetted.

In the case of Koperasi Kijang Mas v. Kerajaan Negeri Perak in 1992, the state government of Perak had accepted Syarikat Samudera Budi Sdn. Bhd.’s tender to log in certain areas in Kuala Kangsar. This breached the APA as it meant the encroachment upon Orang Asli land. The state government’s case was that although these lands were approved for gazetting, it had not been done yet. This emphasizes the problem with the non-gazetting of Orang Asli land, with the state itself recognizing and exploiting the Orang Asli’s vulnerability as a result of the state’s failure to act upon its word. However, Justice Malek of the High Court of Ipoh ruled that the actual gazetting of Orang Asli land was not a mandatory requirement for their rights to be protected. Rather, the approval of their application was sufficient recognition of the Orang Asli’s exclusive rights, thus creating the reserves. Ultimately, this indicates that the Orang Asli’s rights to customary land are protected mainly through precedent, rather than statutory law. These statistics also bear testament to the fact that the non-gazetting of customary lands is not a result of the ignorance or unawareness of the Orang Asli community of their rights: an accumulation of applications amounting to 57.4% of Orang Asli land had not been responded to by State Authorities. It is evident that a certain degree of indifference as well as complacency exists in regards to the gazetting of customary lands.

The degazetting of these lands is yet another contributor to the dispossession of Orang Asli lands. The APA enables the state to degazette Orang Asli reserves should they wish to:

7(3)The State Authority may in like manner revoke wholly or in part or vary any declaration of an aboriginal area made under subsection (1).

There are no prerequisites that need to be met in the state taking back customary lands, and this tends to be done without the knowledge of the Orang Asli19C. Nicholas, “A Brief Introduction”, COAC (2012).. Compounding upon this issue, the APA does not necessitate the need for legal recourse to follow the de-gazzeting of Orang Asli land; thereby stripping them of the fundamental safety net of compensation.

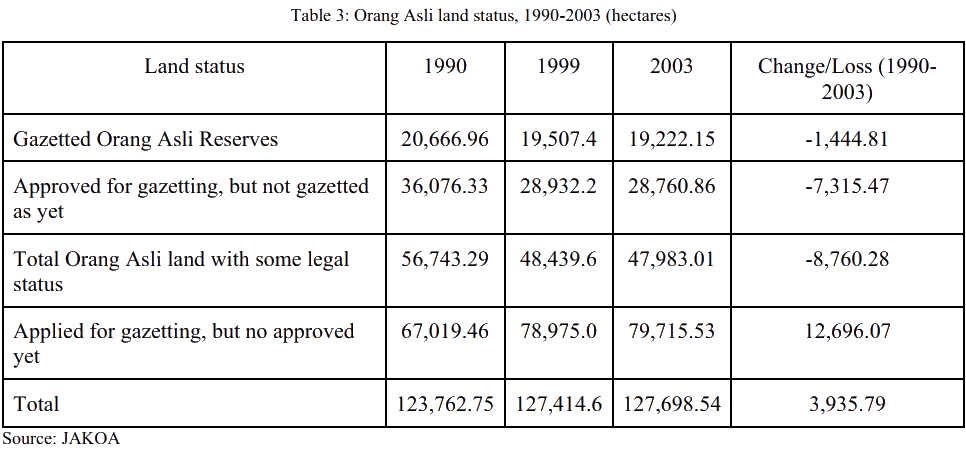

With both the non-gazetting and degazetting of Orang Asli lands, this has led to a decrease of gazetted reserves over the years, as seen in Table 3 below20C. Nicholas, The end of the world for the Orang Asli (SUHAKAM)..

4.4 Acquisition of Customary Lands

Under the LLA, the government is granted the power to acquire any private land for state purposes:

3(1)The State Authority may acquire any land which is needed: 1. for any public purpose 2. by any person or corporation for any purpose which in the opinion of the State Authority is beneficial to the economic development of Malaysia or any part thereof or to the public generally or any class of the public; or 3. for the purpose of mining or for residential, agricultural, commercial, industrial or recreational purposes or any combination of such purposes.

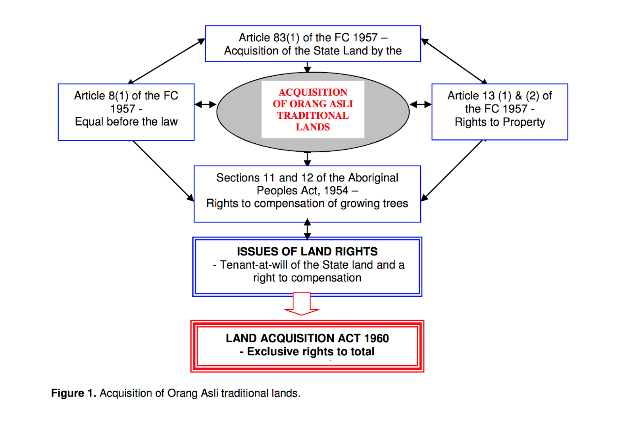

However, the acquisition of Orang Asli customary lands is a much more complicated process which draws upon several other laws, as seen in Figure 1:

This acquisition is heavily warranted by the minimal protection provided by the APA in granting the Orang Asli rights to traditional lands. Even under the protection of an “indefeasible title” of the Torrens system, the state is granted the authority to acquire private land. With the Orang Asli’s status as tenants-at-will despite having their lands gazetted, this leaves the Orang Asli all the more vulnerable to state acquisition. Insofar as there is the need for economic development in Malaysia – which is more likely to be of a greater priority to any government seeking to be re-elected, especially with the Orang Asli making up an almost insignificant proportion of the voting base – the gazetting of customary lands reduces to an act that is futile.

4.5 Compensation

While Article 13(2) of the FC states that “no law shall provide for the compulsory acquisition or use of property without adequate compensation”, the APA fails to provide the same degree of compensation that owners of private property are entitled to. Contrary to the LAA, the APA fails to include any compensation for the loss of land itself:

11(1) Where an aboriginal community establishes a claim to fruit or rubber trees on any State land which is alienated, granted, leased for any purpose, occupied temporarily under license or otherwise disposed of, then such compensation shall be paid to that aboriginal community as shall appear to the State Authority to be just. 12. If any land is excised from any aboriginal area or aboriginal reserve or if any land in any aboriginal area is alienated, granted, leased for any purpose or otherwise disposed of, or if any right or privilege in any aboriginal area or aboriginal reserve granted to any aborigine or aboriginal community is revoked wholly or in part, the State Authority may grant compensation therefore and may pay such compensation to the persons entitled in his opinion thereto or may, if he thinks fit, pay the same to the Director General to be held by him as a common fund for such persons or for such aboriginal community as shall be directed, and to be administered in such manner as may be prescribed by the Minister.

In essence, the Orang Asli are only monetarily compensated for the loss of any property and/or crops that are found on the acquired land21However, the Malaysian courts have ruled that the Orang Asli do have native titles under common law over their lands and that they were entitled to compensation in accordance with the APA. See Sagong Tasi & Ors v. Kerajaan Negeri Selangor & Ors 2002. The issue with monetary compensation for land then becomes the market valuation of customary land, which is often valued lower than surrounding lands.. Not only is this framework of compensation an issue, but the vague manner in which these crops and buildings are valued also acts as a barrier in accessing fair compensation. According to Nicholas, there is no indication of the basis of the valuation, and only a gross amount is calculated for the items concerned22C. Nicholas, Orang Asli – Rights, Problems, Solutions (SUHAKAM) (2010).. This becomes a problem when taking into consideration the potential loss of revenue from fruit-bearing trees, for example, or the cost of replacing a tree up until it is the same age as the tree that was lost.

Additionally, it is vital to take non-monetary compensation into consideration. It is ignorant to assume that monetary compensation – or compensation in general – acts as sufficient leverage in claiming Orang Asli land. Jaringan Kampung Orang Asli Chief, Mustafa Along mentioned in an interview with The Star that “We will only be betraying our ancestors if we sacrificed our customary land for material gain23”The Star, “Orang asli: Gazette native customary land” (2018) https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2018/10/20/orang-asli-gazette-native-customary-land/. In the worst-case scenario that the Orang Asli are forcibly evicted from their lands, the compensation that is of the most value to them is land24Interview with C. Nicholas.; and one that mirrors their previous surroundings so as to not eradicate their former way of life and traditions entirely. However, this happens to rarely be the case, as seen in Eddy Salim & Others v Johor state, Iskandar Regional Development and 12 Others25The Johor Bahru High Court ruled that the land and water at Danga Bay belonged to the Orang Asli living there, and land was given as compensation. However, the Orang Asli were not given the land they had proposed and were instead relocated to Kuala Masai..

Another issue with the framework of compensation is the manner in which it relies on the discretion of the state, as seen in Article 12 of the APA: “the State Authority may grant compensation to the persons entitled in his opinion thereto”. This clause has been widely interpreted as a justification to not necessitate the provision of compensation. Even in the instance that compensation is granted, the absence of a basis of valuation has led to significant disparities in the compensation that each state provides, with “some following the law more strictly, while others are more generous” (Alias, A., & Kamaruzzaman, S. N., Daud M. N.). The complete autonomy that the state is granted over determining the degree of compensation that the Orang Asli should be given is one that courts have repeatedly ruled against. A lack of transparency and the state’s failure to deliver these compensations26The 70 Orang Asli families involved in the Eddy Salim case had to wait for 8 years for the state government to act on delivering their compensation despite the Johor Bahru High Court ruling in their favor. See https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2018/06/24/land-compensation-for-johor-orang-asli-not-given-for-eight-years has led to an inevitable questioning of their integrity, thus making it unequivocally clear that fair compensation is only provided through the intervention of the judicial system, and not on the state’s own accord.

5.0 REVIEW OF THE MALAYSIAN GOVERNMENT

5.1 What Has Been Done

The most recent response by the Malaysian government in regards to the dispossession of Orang Asli customary land is the implementation of the New Orang Asli Land Policy. Announced by Tan Sri Mahiaddin Yassin27Malaysia’s former Deputy Prime Minister and current Prime Minister. on the 4th of December 2010, this policy granted 29,990 Orang Asli households permanent titles to 0.8 to 2.4 hectares of agricultural land and 0.1 hectares for housing. Apart from its acknowledgement of the issue of non- and degazetting of customary lands, the New Orang Asli Land Policy ultimately places the Orang Asli in a situation in which they lose significantly more customary land. 80,000 acres of customary land that were initially recognized are now not, thus fueling the dispossession of Orang Asli traditional lands rather than resolving it. A solution that improves the average ownership of customary lands at the collective expense of the Orang Asli is one that fails to address the root problem of the issue: the lack of acknowledgement and reinforcement of the Orang Asli’s rights to customary land. Within this overarching issue, is the controversy of the 99 years lease of the assigned lands as per the policy. Nicholas mentioned that “Nothing as such, can be more graphic of the Orang Asli’s fate than this twist in the kindle that their inalienable right on their land now has an expiry date.” While the UNDRIP stipulates the importance of indigenous rights to customary lands, the New Orang Asli Land Policy effectively reduces a fundamental right to one that functions on a contractual basis. This becomes an issue as it alienates the Orang Asli from both their inherent rights to indigenous land as well as any form of recognition from the LAA. This policy is also unconstitutional in the way that it bans those awarded the land grants from filing any claims against the state, acting against Article 8(1) of the FC: “All persons are equal before the law and entitled to the equal protection of the law”. In more ways than one, the New Orang Asli Land Policy threatens both the Orang Asli’s rights and access to customary land – of which the Orang Asli were actively aware of and object through a protest28Occurred on 17.03.2010. as well as the submission of a memorandum. Both acts of retaliation were not responded to despite their vocal dissatisfaction.

5.2 The Malaysian Government: Powerless?

An effective solution to the dispossession of Orang Asli land is one that requires the government to address the inadequacy of Malaysian legislation in recognizing Orang Asli customary land rights. While the constitution and LAA are sufficient in protecting land rights as a whole, it is evident that the APA acts as a barrier in enabling them to access these rights. The federal government is able to amend the APA through the process of passing a bill through the Dewan Rakyat and Dewan Negara29Otherwise known as the House of Representatives/Lower House and the Senate/Upper House respectively. – both of which make up the Malaysian Parliament. This amendment would act as a platform through which the Orang Asli could be granted greater autonomy over their lands, or necessitate the gazetting of Orang Asli lands. However, it is insufficient for the government to solely enact policies if land security for the Orang Asli is to be guaranteed30C. Nicholas, “A Brief Introduction”, COAC (2012).. The negligence of the constitution in protecting the Orang Asli means that there are no provisions within the legal framework that require their rights to be upheld, let alone identified. Thus, despite its meticulous process, constitutional reform is mandatory for tangible change to occur – which Article 159(1) of the constitution allows for.

Upon examining the different ways in which the government is empowered to secure Orang Asli lands, it is imperative to look into the role of JAKOA as a federal agency. Nicholas called for JAKOA to “work actively to secure Orang Asli lands, and not hide behind the rhetoric of ‘land is a state matter’” in his book ‘Orang Asli – Rights, Problems, Solutions’. In comparing JAKOA to FELDA (Federal Land Development Authority), Nicholas highlights FELDA’s success in directing the state to provide land for landless Malays acts as an example of the federal government’s ability to intervene in state matters. As such, JAKOA’s status as a federal agency means that it is in an identical – if not better31The UNDRIP establishes the urgency to protect indigenous lands, which belong to only around 198,000 individuals.– position to defend the Orang Asli’s claim to their ancestral lands. In these regards, the federal government is fully equipped to ensure the protection of Orang Asli lands; it is simply a lack of urgency that prevents itself from enacting tangible change.

5.3 Attitudes Towards the Dispossession of Orang Asli Customary Land

Since Malaysia’s independence in 1957, there have been a total of three different governments that have been in power during the writing of this paper. A review of the attitudes towards the dispossession of Orang Asli customary land requires a separate analysis of each governing coalition: Parti Perikatan/Barisan Nasional (BN), Pakatan Harapan (PH) and Perikatan Nasional (PN).

The Parti Perikatan coalition – which became the Barisan Nasional in 1973 – had been in power for 60 uninterrupted years from Malaysia’s independence up until 2018. While their manifestos had repeatedly consisted of the better protection of Orang Asli lands, Tables 2 and 3 suggest otherwise. The role of the state in providing land titles can mistakenly misdirect the accountability for the increasing loss of customary land from 1990 to 2003.

Regardless of the nature of the acquisition of indigenous land – i.e., be it state or private – the dispossession of Orang Asli land will always require the consent of the state for land titles to be transferred. However, the negligence of the BN federal government lies in their complacency in ensuring the protection of customary lands – as seen through the absence of any intervention neither through JAKOA nor through their general role as the federal authority. This indifference can be credited to the lack of Orang Asli representation in directing positions in the JAKOA as well. It was only during the 14th General Election in 2018 that Ajis Sitin was appointed as the first Orang Asli Director-General of JAKOA, following the mandatory retirement of the former Director-General.

The change in government in 2018 provided a new hope for the Orang Asli, with the Pakatan Harapan coalition expressly providing for the protection and empowerment of the Orang Asli in Promise 38 of their manifesto. This included a remodelling of JAKOA so as to provide “the skills and independence to improve their (the Orang Asli’s) lives and socio-economic conditions rather than being controlled by the department.”32PH Manifesto 2018. One of the ways that this was realized was through the instatement of Prof. Dr. Juli Edo33Prof Dr Juli Edo is an Orang Asli himself, and is from the Semai tribe. as the Director-General of JAKOA in 2019. In an interview with the Star, Juli expressed interest in partnering with NGOs and researchers in addressing the concerns of the Orang Asli: “As a department, we cannot work in silos. There needs to be a partnership between us and other agencies as well as the Orang Asli themselves. If we don’t work together, we will only repeat mistakes from the past.”34The Star, “Orang Asli contributed to nation building, says Juli.” (2019) https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2019/08/03/orang-asli-contributed-to-nation-building-says-juli Already, JAKOA’s more inclusive approach under the PH government acts as a significant shift in culture as compared to BN’s government-centered approach. However, this singular act does not translate into the absolute success of PH in preventing the dispossession of Orang Asli land. For one, PH had failed to fulfil their promise of bringing the SUHAKAM National Inquiry Report on Indigenous Land Rights 2013 for Parliamentary debate in their first year of governance, nor were there any initiatives in protecting Orang Asli land under land development schemes such as FELCRA and RISDA. It is also important to note the discrepancies within the PH federal government in ensuring the protection of customary lands. For the first time in Malaysian history, the federal government had taken a case against a state government – which was the PAS-led35The political party ‘Parti Islam Se-Malaysia’. Kelantan government – for logging customary land in Gua Musang. However, no actions were taken by the PH federal government against the PH-led Kedah government for doing the same, as purported by the Kampung Tasik Cunex Orang Asli. In an interview with Free Malaysia Today, Shariffa Sabrina Syed Akil, president of Pertubuhan Pelindung Khazanah Alam Malaysia36An organization that is helping the Kampung Tasik Cunex Orang Asli gain legal representation. criticised this disparity of justice:

“Perak is under Harapan. Don’t just sue Kelantan. Sue Perak too, which is destroying the lives of Orang Asli.” It is evident that under the PH government, there is talk on a national level but insufficient action that follows through.

The 2020 political crisis in March saw a change in government to an alliance led by now Prime Minister Mahiaddin Yassin. As an unelected government, Perikatan Nasional is not accountable to a manifesto and thus there are no metrics that their performance can be measured against. This means that there is no goal nor incentive for PN to work towards increasing the protection of Orang Asli land. The PN cabinet is also without any Orang Asli representatives, thereby side-lining the interests of the Orang Asli within the executive branch of government. In light of keeping the Covid-19 pandemic under control, PN is yet to release a statement about the dispossession of Orang Asli land.

6.0 CONCLUSION

6.1 The Prospect of Change: A Dead End?

The issue of the dispossession of Orang Asli customary land ultimately roots itself in the loss of culture and the Orang Asli’s livelihoods. Their rights to ancestral land need to be constitutionally protected as the aim of addressing the issue is not solely for fair compensation to be delivered, but for the dispossession of Orang Asli land to be prevented entirely. In this sense, the Orang Asli should not have to rely on legal precedents and/or the goodwill of the Malaysian government so as to access these rights, as stipulated by Article 26 of the UNDRIP. The constitution provides the government with sufficient means to ensure the protection of customary lands; thus, the question lies in the severity with which the government perceives the dispossession of Orang Asli land. With the sudden change in government and the global effect of the Covid-19 pandemic, it is unlikely that the Malay-dominated cabinet of PH would hold the dispossession of these lands to the degree of urgency that it should be held to.

6.2 Concluding Remarks

While the dispossession of Orang Asli customary land roots itself in legislation that oppose the self-determination of the Orang Asli, it is evident that the government plays a pivotal role in this issue. If the state were to maintain its power over the ownership of customary lands, it is crucial that JAKOA is proactive in representing the concerns of the Orang Asli and intervenes when counterproductive policies are enacted. The culture and livelihoods of the Orang Asli have never been at the forefront of any government’s priority since Malaysia’s independence in 1963. As a community that is forced to bear the destructive legacy of marginalization and poverty, land ownership is the most effective solution to reversing the damage that has been done; or, as a mitigatory action, the statutory protection of their lands. The government is in an obligation to protect the Orang Asli as its citizens: which means delivering fair compensation for customary lands that have been acquired whilst working with the Orang Asli in ensuring the protection of their lands.

References

- Abidin, Z. Z., & Wee, S. T. (2013). Issues of customary land for Orang Asli in Malaysia.

- Aboriginal Peoples Act 1954, The Commissioner of Law Revision, Malaysia (2006). https://www.jkptg.gov.my/images/pdf/perundangan-tanah/Act_134-Oboriginal_Peoples_Act.pdf

- Alias, A., & Kamaruzzaman, S. N., Daud M. N. (2010). Traditional lands acquisition and compensation: The perceptions of the affected Aborigin in Malaysia. International Journal of the Physical Sciences, 5(11), 1696-1705.

- Buku Harapan Rebuilding Our Nation Fulfilling Our Hopes. Retrieved August 17, 2020, from https://kempen.s3.amazonaws.com/manifesto/Manifesto_text/Manifesto_PH_EN.pdf.

- Bunyan, J. (2019, July 29). No such thing as Orang Asli ancestor land in the state, Perak MB told NGOs. Malay Mail. Retrieved August 10, 2020, from https://www.malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2019/07/29/no-such-thing-as-orang-asli-ancestor-land-in-the-state-perak-mb-told-ngos/1775783

- Chung, Y. F., & Faran, T.(2010). The Orang Asli of Malaysia: Poverty, Sustainability and Capability Approach (Master’s thesis, Lund University Centre of Sustainability Science). Semantic Scholar.

- Eddy bin Salim & Ors v Iskandar Regional Development Authority & Ors [2017] MLJU 2308

- Hamzah, H. (2013). The Orang Asli Customary Land: Issues and Challenges. Journal of Administrative Science, 10(1).

- Kelah bin Lah v Pengarah Tanah dan Galian, Johor & Ors [2020] MLJU 7

- Koperasi Kijang Mas & Ors v Kerajaan Negeri Perak & Ors [1991] 1 CLJ 486

- Laman Web Rasmi Jabatan Kemajuan Orang Asli. (n.d.). Retrieved November 03, 2019, from https://www.jakoa.gov.my/

- Land Acquisition Act 1960 (Act 486) (2015). http://pejuta.com.my/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Act-486-Land-Acquisition-Act-1960.pdf

- Mah, R., & Balasundaram, S. (2013, October 16). Compulsory Land Acquisition in Malaysia, Compensation and Disputes. Retrieved May 30, 2020, from https://mahwengkwai.com/compulsory-land-acquisition-malaysia-compensation-disputes/

- Malaysian Federal Constitution, The Commissioner of Law Revision, Malaysia (2010). http://www.agc.gov.my/agcportal/uploads/files/Publications/FC/Federal%20Consti%20(BI%20text).pdf

- Masron, T. & Masami, F. & Ismail, Norhasimah. (2013). Orang Asli in Peninsular Malaysia: population, spatial distribution and socio-economic condition. J. Ritsumeikan Soc. Sci. Hum.. 6, 75-115.

- Musa, Z. (2018, June 24). Land compensation for Johor orang asli not given for eight years. Retrieved August 16, 2020, from https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2018/06/24/land-compensation-for-johor-orang- asli-not-given-for-eight-years

- Nah, A. M. (2008). Recognizing indigenous identity in postcolonial Malaysian law: Rights and realities for the Orang Asli (aborigines) of Peninsular Malaysia. Bijdragen Tot De Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde / Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia, 164(2-3), 212-237. doi:10.1163/22134379-90003657

- National Land Code (Act 56 of 1965), 1.0 http://palmoilis.mpob.gov.my/akta/NLC1956DIGITAL-VER1.pdf.

- Nicholas, C. (2010). Orang asli rights problems solutions: A study commissioned by SUHAKAM. Kuala Lumpur, Selangor: Suruhanjaya Hak Asasi Manusia. http://www.suhakam.org.my/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Orang-Asli-Rights-Problems-Solutions.pdf

- Nicholas, C. (2012, August 20). A Brief Introduction. Retrieved December 24, 2019, from https://www.coac.org.my/main.php?section=about

- Orang Asli contributed to nation-building, says Juli. (2019, August 03). The Star. Retrieved August 17, 2020, from https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2019/08/03/orang-asli-contributed-to-nation-building-says-juli

- Orang Asli. (2018, January). Retrieved January 24, 2020, from https://minorityrights.org/minorities/orang-asli/

- Orang asli: Gazette native customary land. (2018, October 20). The Star. Retrieved May 21, 2020, from https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2018/10/20/orang-asli-gazette-native-

- customary-land/

- Sagong Bin Tasi & Ors v Kerajaan Negeri Selangor & Ors [2002] 2 MLJ 591; [2002] 2 AMR 2028; [2002] 2 CLJ 543

- Subramaniam, Y. (2013). Affirmative Action and the Legal Recognition of Customary Land Rights in Peninsular Malaysia: The Orang Asli Experience. Australian Indigenous Law Review, 17(1). Retrieved February 13, 2020, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26423260

- Suhaimi, A. B. (2019, May 2). Orang Asli Customary Land Rights. Retrieved May 31, 2019, from https://www.thomasphilip.com.my/articles/orang-asli-customary-land-rights/

- Teacher, Law. (November 2013). Malaysia Procedure for Enactment of an Act. Retrieved June 28, 2020, from https://www.lawteacher.net/free-law-essays/administrative-law/malaysia-procedure-for-enactment-law-essays.php?vref=1

- Tong, G. (2017, February 28). Gov’t breaches fiduciary duties to Seletar tribe, rules court. Malaysia Kini. Retrieved May 16, 2020, from https://www.malaysiakini.com/news/374073