The Spillover Effects of ECB’s Conventional and Unconventional Monetary Policies on Asia-Pacific Stock Markets and Potential Heterogeneities

by Raphael Bar, University of Warwick

Abstract: This paper examines the impact of conventional and unconventional monetary policy surprises by the European Central Bank (ECB) on 10 Asia-Pacific stock markets over the period 2001-2021. We employ market prices of futures contracts (government bonds) to identify the unexpected component of (un)conventional monetary policy announcements. With appropriate controls to ensure robustness to endogeneity issues, we find that in response to unexpected rate hikes, most stock markets either display statistically insignificant, or positive and significant returns, differing from typical findings in most literature. This paper also finds evidence that industrial composition (not real economic linkages) of national stock indexes partly drives cross-country variation in responses to monetary policy shocks. By taking into account international stock return co-movement, our results suggest the presence of structural shifts in the response of Asia-Pacific equity prices to ECB monetary policy surprises between GFC and non-GFC years, as well as between pre-COVID and COVID periods.

1. INTRODUCTION

A recent Bloomberg.com article titled “How Unconventional Monetary Policy Turned Conventional” suggested that unconventional monetary policies (UMP) are emerging as a mainstream policy choice in an ultra-loose monetary environment that is expected to last longer than during the post-financial-crisis period (Bloomberg, 2020). This serves as the paper’s primary motivation to critically evaluate the combined effectiveness of CMPs and UMPs, in a setting that resembles more of a health and economic crisis, rather than a financial one back in 2007.

Monetary policy announcements from major central banks like the Federal Reserve (Fed) and ECB do not merely have important effects on domestic real economy and financial markets, they also frequently spill over across borders (Kim and Nguyen, 2009; Wang and Zhu, 2013). A deeper understanding of the relationship between the unexpected component of policy decisions – often referred to as monetary policy shocks or surprises – and foreign stock market returns hence provides foreign policy makers and market participants insights into their respective countries’ economic and financial integration with major economies in the world.

Previous studies largely focussed on the impact of conventional monetary policy (CMP) shocks, on US financial asset prices using a variety of empirical approaches, including vector autoregressive models (VAR), asymmetric conditional volatility modelling method and event studies, see (Kontonikas et al., 2013; Kontonikas & Kostakis, 2013; Bernanke & Kuttner, 2005; Rigobon & Sack, 2004). The prevailing finding of these studies is that an unanticipated increase (decrease) in target policy interest rates – the Federal Funds rate in this case – is linked with a decrease (increase) in stock prices. Several studies detailing Euro Area stock market reactions to policies by ECB produce rather mixed results. Bohl et al. (2008) conclude that an unanticipated 25‐basis‐point hike in the interest rate by ECB is associated with decreases between 1.42 and 2.30% in European stock market prices. Bredin et al. (2009) instead documented the insignificant impact of monetary policy surprises by the German Bundesbank and ECB on the German DAX Index.

Thus far, a relatively scarce literature exists to examine the spillover effects of monetary policy surprises by either central bank on the equities markets of other countries. Wongswan (2006,2009), Kim and Nguyen (2009), Wang and Zhu (2013), Nguyen and Ngo (2014) and more recently Bao and Mateus (2017) are among the very few who discovered a large, significant response in Asian equity indexes due to US monetary policy shocks. Wongswan (2009) postulated that cross-country variation in responses to Fed policy surprises is principally related to proxies for financial integration with the United States than to that of real economic linkages. However, there remains a distinct lack of investigation into the effects of unanticipated policy changes by the Fed’s European counterpart on Asia-Pacific markets, despite growing bilateral economic and financial ties between the Euro Area and the Asia-Pacific (Kim & Nguyen, 2009).

The seemingly intuitive, inverse relationship between target policy interest rates and stock market valuation, however, does not always hold. Using an event-study approach, Kontonikas et al. (2013) argued that a structural break in US stock market response occurred during the recent financial crisis, when an expansionary monetary policy was largely perceived as a signal of worsening economic conditions. Consequently, this reinforces the flight to safety trading and a decline in stock returns during the same period (Kontonikas et al., 2013). While the asymmetric stock market behaviours in the US for crisis and non-crisis periods are comparably evident in Europe (Wang & Mayes, 2012; Hosono & Isobe, 2014; Haitsma et al., 2016), Hayo and Niehof (2011) contended that the estimated parameters for the financial crisis period are not significantly different from those estimated over the pre-crisis period. This paper therefore proposes to extend the literature by looking into potential divergences in stock market responses to monetary policy surprises before and during the COVID-19 outbreak. It can also add relevance to the ongoing debate surrounding CMP’s limits close to the zero-lower bound.

To date, the reaction of stock market performance (both domestic and international) to unconventional monetary policies (UMP) by the ECB have received much less attention in current literature (Chebbi, 2018). Some papers (Cahill et al., 2013; Joyce et al., 2011;) utilised survey expectations from professional forecasters to model the surprise components of UMPs. This approach is plagued by limited data availability and according to Rogers et al. (2014), “are not necessarily perfect measures of investors’ belief”. Bulligan and Delle Monache (2018) implemented a dummy in their baseline specification that takes the value one on selected event dates when UMP measures are announced by the ECB, and zero otherwise. While the paper provides evidence of UMP announcements having significant effects on the exchange rates and sovereign yields in Italy and Spain (which subsequently spilled over to their respective stock markets), it inevitably fails to differentiate the influence of specific policies in terms of size. Chebbi (2018), Fausch and Sigonius (2018), Haitsma et al. (2016) and Rogers et al. (2014) instead employed market-based proxies such as changes in sovereign bond yields in an intradaily window to measure UMP surprises. They consistently found that UMPs are effective in easing financial conditions, particularly in European stock markets during the crisis. Even much less is known about the spillover effects of UMPs to international markets. Fukuda (2019) argued that since the financial crisis, UMPs adopted by advanced countries have destabilized emerging economies, particularly in Asia, and have become a risk factor for the global economy.

To address the aforementioned gaps in the literature, this paper adopts an event-study methodology to investigate the impact of ECB monetary policy shocks on 10 Asia-Pacific stock markets, including both developed and emerging market countries, between January 2001 to January 2021.

The papers closest to the present study are Haitsma et al. (2016) and Kim and Nguyen (2009). The former similarly studies the impact of ECB target interest rate news on equities market returns and volatilities in Asia-Pacific from 1999-2006 but relies on an EGARCH (1,1) model instead of the proposed event-study approach. The authors also investigated the speeds of news absorption across the Asia region by analysing the difference in spillover effects between overnight and intradaily holdings period, an element which has been largely ignored by previous event study research and that the present study seeks to incorporate. This justification was deviated from Kim and Nguyen’s (2009) methodology as we are not interested in analysing the conditional variance of daily returns. We shall follow a similar approach as Haitsma et al. (2016) with two crucial departures beyond the difference in studied markets. First, while Haitsma et al. (2016) considered how different portfolios of stocks respond to ECB policy surprises to extract potential credit and interest rate channels, the latter studies focused on evidence for export channels (Bao & Mateus, 2017; Berge & Cao, 2014). Second, they also fail to control for macroeconomic indicator releases that may contaminate the monetary policy surprises under investigation, potentially violating the orthogonality condition in their specification.

Our contributions to literature are in several dimensions. First, we expand upon earlier efforts by Haitsma et al. (2016) and Rogers et al. (2014) to construct a database for both conventional and unconventional measures undertaken by ECB for the entire sample period. Second, we examine the relationship between ECB monetary policy surprises and Asia-Pacific stock market performances – two geographical markets that are severely understudied as a combination in existing literature. Third, to our best knowledge, this paper is the first research which extensively distinguishes and documents the direct influences of both UMP and CMP surprises by the ECB on Asia-Pacific markets. This is of interest as the ECB has for some time introduced CMP and UMP simultaneously (Cour-Thimman & Winkler, 2013). Fourth, we demonstrate the time-varying nature of the impact of ECB monetary policy shocks and the structural breaks that occurred following the onset of the subprime financial crisis (GFC) in 2007 and most recently the COVID-19 pandemic. Fifth, we offer explanations for country-specific heterogeneity in terms of the direction and magnitude of stock market reactions based on proxies for real economic integration with the Euro region and industrial composition of domestic indexes.

The key findings of the paper are summarised as follows. First, most stock indexes do not react significantly to unanticipated hikes in policy rates by ECB, except for two markets which quickly exhibit (surprisingly) positive movements without any tardy responses. Second, industrial composition (not real linkages) is pivotal to explain cross-country variation in equity market responses. Third, the relationship between ECB monetary policy surprises and stock market performances is not stable across time for both GFC and COVID-19 episodes.

The remaining paper is organised as follows. Section 2 briefly discusses the identification of monetary policy surprises. Section 3 introduces the event-study methodology. Section 4 describes the data sources and issues. Section 5 reports and discusses the empirical results. Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. IDENTIFICATION OF MONETARY POLICY

The efficient markets hypothesis (Fama, 1970) propounded that asset prices in a forward-looking and efficient stock market fully reflect all available information to market participants. This implies that equity markets should in theory already have priced in anticipated policy changes on days of monetary policy announcement by central banks, and that any subsequent changes in stock prices is the result of unanticipated policies – the explanatory variable of study in this paper.

A natural question that arises is the appropriate quantification of the unexpected component of monetary policy decisions. Failure to distinguish between the unexpected and expected elements of monetary policy announcements will have inevitably introduced bias in the estimated coefficients in Section 5 due to an error in the variables problem (Fausch & Sigonius, 2018). Ever since the publications by Krueger and Kuttner (1996) and Bernanke and Blinder (1992), the Federal funds futures rate has been most used in the U.S. literature as an unbiased and efficient proxy to capture monetary policy expectations, and by extension the expectations of effective Federal funds rate (FFR) (Gürkaynak et al., 2007). As suggested by Kuttner (2001), the surprise component of CMP by the Fed can then be derived from immediate changes in the prices of said futures contract within a fixed window around the announcement.

While there does not exist a comparable financial market instrument that explicitly links itself to the Euro Area target policy rate – called main refinancing operations rate (MRO) – Bernoth and von Hagen (2004) found that the continuous 3-month Euribor futures rate to be an unbiased market-based predictor for MRO rate, which is the ECB’s most pivotal instrument in providing liquidity to the banking system and pursuing open market operations. Adopting Kuttner’s (2001) pedagogy, later refined within a European setting (Bredin et al., 2009), we thus proxy the surprise component of ECB’s CMP announcements by changes in the 3-month Euribor futures rate. This identification scheme hinges on a crucial assumption that investors in the futures market possess the same information set as the central bank or monetary authority in question, such that any deviation in their expectations of MRO rate from the actual level during a CMP announcement is solely associated with an exogenous monetary policy shock.

Next, to measure the unanticipated component of UMPs by the ECB, we closely model Rogers et al. (2014) work, which was based on the change in the spread between 10-year Italian and German government bond yields on announcement days. The justification, as Chebbi (2018) and Rogers et al. (2014) defended, was that several ECB UMPs such as Securities Market Purchase Programme (SMP), Long-Term-Refinancing-Operations (LTROs) and Covered Bond Purchase Programmes (CBPPs) were designed to decrease intra-Euro-Area sovereign spreads and stabilise the financial markets of distressed countries. For instance, the GDP-weighted 10-year Euro Area sovereign yield was reduced by 56 bps between September 2014 and February 2015 following ECB’s asset purchase programme (APP) (De Santis, 2020).

3. ECONOMETRIC METHODOLOGY

3.1 Event-study approach

The empirical methodology follows the standard event study literature from January 2001 to January 2021. In this paper, the relevant sample of events is defined as the union of all days when the ECB Governing Council (GC) convenes and finalises CMP decisions related to MRO rate and other key interest rates – typically on a monthly basis – as well as when non-standard, unconventional measures were announced. However, a critical issue in studying the influence of monetary policy shocks on stock market returns is endogeneity. First, simultaneity can potentially surface due to a contemporaneous response of monetary policy to stock market developments, resulting in causality running in the opposite direction. Nonetheless, as Kontonikas et al. (2013) and Kurov (2010) argued, the problem of endogeneity is considerably less prevalent when higher frequency data, such as intradaily or daily data, were utilised within an event study framework. Changes in asset prices are unlikely to instantaneously affect monetary policy on the same day. Besides, it is counter-intuitive for the ECB to react to stock price movements in Asia-Pacific markets to begin with. Second, the possibility of joint response of monetary policy and the stock market to economic news (Bernanke & Kuttner, 2005) may result in biased and inaccurate estimates of stock price responses to MRO surprises. One mitigating strategy commonly proposed in the literature, ( Rogers et al., 2014; Gürkaynak & Wright, 2013) is the use of high-frequency, intradaily data to pinpoint the event window around an ECB monetary policy announcement where it is the only driver of stock market returns in Asia-Pacific countries.

Several caveats, however, remain. First, since ECB’s monetary policy announcements were made past trading hours in the other stock exchanges in Asia-Pacific, a close-to-open (overnight) window is of greater relevance, in contrast to a 20-minute window (Gürkaynak & Wright, 2013) or 2-hour window (Rogers et al., 2014) around the policy announcement. Second, announcements are complicated – particularly those concerning asset purchases – and market participants require time to digest such news. Hanson and Stein (2015) further contended that the effects of monetary policy announcement on long-term government bond yields are not instantaneous, casting doubts on the use of an intradaily, narrow window to extract UMP surprises in this case. This paper hence turns to daily data to measure equity index returns and CMP/UMP surprises in one-day windows surrounding ECB’s announcement, and addresses the endogeneity problem by controlling for potential confounding factors like releases of macroeconomic and financial market indicators.

3.2 Empirical specifications

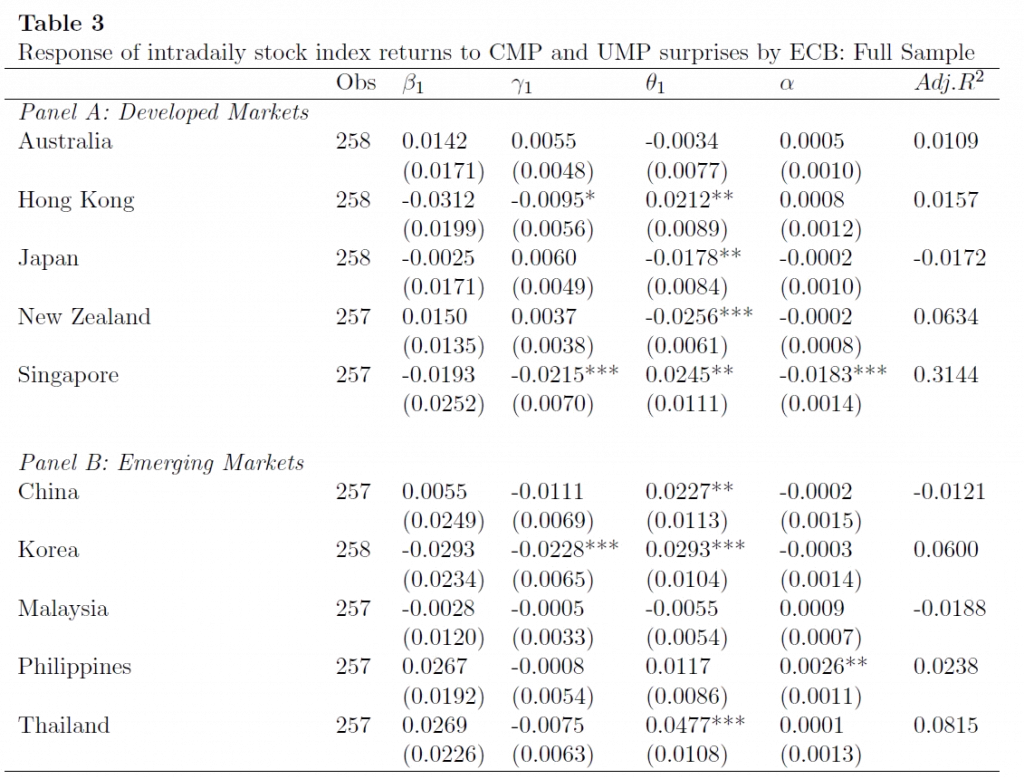

As a benchmark for estimating the immediate reaction of Asia-Pacific stock markets to CMP and UMP actions by ECB, we begin our empirical investigation by running the following full-sample linear regression for each country, without distinguishing between sub-sample periods (GFC or COVID-19):

(1)

where Ri,t represents the returns on day t of a national stock index i, calculated over two time horizons (overnight and intradaily) to account for differences in speeds of news absorption. ∆rtu, ∆rte, ∆rtu,c are respectively the CMP surprise, the expected policy rate change and UMP surprise on day t when announcements are made. DtGFC is a GFC dummy that takes a value of zero before 22nd August 2007 and one thereafter 1Following Haitsma et al. (2016), we define the ECB’s announcement of the first unconventional monetary policy on 22nd August 2007 as the start of the GFC period. DtCOVID is a dummy that takes a value of zero before 23rd January 2020 and one thereafter, given that the central government of China imposed a lockdown in Wuhan and other cities in Hubei on the same day, sparking drastic reactions from investors globally. Xi,t is a vector of control variables. It consists of a European stock index to control for international equity market co-movement, a holiday dummy to account for the potential impacts of differences in trading days across stock markets due to market closure2The holiday dummy takes the number of the days of market closure between two successive market prices used in the calculation of Ri,t. For example, a value of two will be assigned for a stock market returns observation calculated over a longer horizon due to market closure (ie. returns calculated over 4 days – Monday close to Thursday open price, of which the exchange is closed on Tuesday and Wednesday), and surprises stemming from macroeconomic announcements internationally in the Euro Area and U.S., as well as domestically in the studied Asia-Pacific country. This helps to isolate the policy-related effects on stock market movements on days of multiple information arrival which can be potentially confounding (Kim & Nguyen, 2006). Each country’s regression is estimated using ordinary least squares (OLS) and is based only on observations when CMP and UMP announcements are made by the ECB. Most previous event studies ignore expected policy rate changes and only consider the impact of monetary policy surprises in their models ( Kontonikas et al., 2013; Kurov, 2010; Wongswan, 2009). This is largely consistent with the efficient market hypothesis as explained in Section 2, where anticipated components of a monetary policy decision are hypothesised to have insignificant influence on asset price movements. However, in line with arguments made by Fatum and Scholnick (2008), as well as statistically significant evidence from more recent papers (Fausch & Sigonius, 2018; Haitsma et al., 2016; Wang & Zhu, 2013), this paper decides to evaluate the prospective impact of expected policy changes by including ∆rte in Eq. (1) and subsequent models3As we will see later in Section 5, some of the estimated coefficients on ∆rte are indeed significant. To explore a structural change in the response of Asia-Pacific stock market returns to CMP and UMP surprises during GFC and pre-GFC years, we adopted the specification of Haitsma et al. (2016) and deduced the following equation:

(2) ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{align*} R_{i,t}&=\alpha + [\beta_1 (1-D_t^{GFC} )+\beta_2 D^{GFC}_t] \inc r_t^u \\ &+ [\gamma_1 (1-D_t^{GFC}) +\gamma_2 D_t^{GFC}+\gamma_2]\inc r_t^e \\ &+ \theta_1 \inc r_t^{u,c} + \delta X_{i,t} \end{align*}](https://econsilience.ameuglobal.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-d0a0ffe469a594d04ee1b20b1c9d0165_l3.png)

Similarly, to examine potential divergences in stock market responses before and during the COVID-19 outbreak, we regress the following equation:

(3) ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{align*} R_{i,t}&=\alpha + [\beta_1 (1-D_t^{COVID})+\beta_2 D^{COVID}_t] \inc r_t^u \\ &+ [\gamma_1 (1-D_t^{COVID})+\gamma_2 D_t^{COVID}+\gamma_2]\inc r_t^e \\ &+ \theta_1[(1-D_t^{COVID})+\theta_2 D_t^{COVID}]\inc r_t^{u,c} \\ &+ \delta X_{i,t} +\epsilon_{i,t} \end{align*}](https://econsilience.ameuglobal.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-d6e2272ced605a2fa30364c6ca7651a6_l3.png)

3.3 Theory and testable hypotheses

Monetary policy measures (surprises) by the ECB may impact foreign equity prices in a similar fashion as they do domestic European stock markets through two channels. Unexpected changes in MRO rate can affect the discount rate for future cash flows and the expected cash flows themselves via the influence of monetary policy on the outlook of real macroeconomic variables like output and employment (Paletis, 1997). To the extent the Euro Area’s economic activity influences global activity, particularly in Asia-Pacific, this paper mainly considered the latter channel and puts forward the following hypotheses for Eq. (1):

H1: A country with higher real economic integration with the Euro Area will respond more to an unexpected change in MRO rate; the direction of the response may vary (β1≠0). H1a: If an unexpected hike in MRO rate leads to a downward revision in expectations for Euro Area’s economic activity, it will depress demand for imports from Asia-Pacific – foreign equity indexes decline (β1<0). H1b: If an unexpected hike in MRO rate leads to an upward revision in expectations for Euro Area’s economic activity, it will boost demand for imports from Asia-Pacific – foreign equity indexes increase (β1>0)4In some instances, a higher-than-expected MRO rate signals greater optimism about the strength of European economies. Bao and Mateus (2017) propose an alternative channel with similar outcome, whereby a higher interest rate following an announcement of contractionary monetary policy by ECB leads to capital inflow from abroad. This is then accompanied by an appreciation in Euro, resulting in foreign commodities becoming relatively cheaper, thus benefitting Asia-Pacific exporting firms..

To establish structural breaks in equity price responses to CMP/UMP surprises during the GFC and COVID-19 episodes, we linearly regressed Eqs. (2) and (3) respectively, before conducting Wald tests for the equality of coefficients, namely on:

H0: β1=β2 for both equations (2) and (3) H0: θ1=θ2 for equation (3).

If β1≠β2(θ1≠θ2), this supports a structural shift in the stock market responses to CMP (UMP) shocks between both periods in the relevant episode.

4. DATA

4.1 Monetary policy surprises

The sample period includes all CMP and UMP announcements by the ECB from 19th January 2001 to 18th January 2021. It covers 258 announcements in total; 191 of which are solely CMP, 30 of which are solely UMP, and the remaining 37 comprise both types of announcements on the same day. The ECB GC meets twice a month and usually makes monetary policy decisions at the first of the two meetings (or every six weeks). This is followed by an official press release at 13:45 Central European Time (CET, GMT +1), announcing the decision on MRO rate – the target policy interest rate – among other key interest rates. Approximately 45 minutes later at 14:30 CET, the ECB President and Vice-President held a press conference to explain the decisions in an introductory statement and answered questions from attending journalists. We used GC meeting dates as the event days for CMP announcements, and for some UMP announcements on occasions when the two align. Where the non-standard measures5See Appendix for more discussions on unconventional, non-standard monetary policy measures announced by ECB. did not correspond to the regular announcement dates, we independently merge the dates provided by Haitsma et al. (2016) and Rogers et al. (2014) for the period up to February 2015, and the database of non-monetary-policy-decision press release from ECB up to and including January 20216See https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/govcdec/otherdec/html/index.en.html (see Appendix in the full journal).

Based on previous discussion in Section 2, the CMP surprise ∆rtu on the day of ECB announcement t is computed as:

(4) ![]()

where (ft-ft-1) represents the one-day discrepancy in the implied futures spot rate (100 minus the daily settlement price) of 3-month Euribor futures contracts at day t and the prevailing rate at the day before the announcement, t-1. We then measure the anticipated element of policy changes, ∆rte as the difference between the actual policy rate change, ∆rt and the surprise component:

(5) ![]()

The UMP surprise ∆rtu,c is computed as the change in the yield spread between 10-year Italian and German government bonds (Rogers et al., 2014):

(6) ![]()

where ytI and ytG represent the Italian and German 10-year government bond yields at day t, respectively.

Raw changes in MRO rate are sourced from ECB Statistical Data Warehouse, 3-month Euribor future prices are from Eikon and sovereign bond yields are from Global Financial Data and Investing.com7See: https://www.investing.com/rates-bonds/germany-10-year-bond-yield and https://www.investing.com/rates-bonds/italy-10-year-bond-yield for German and Italian 10-year bond yields respectively. They are manually filtered to match each day of the ECB announcements during the sample period.

4.2 Asia-Pacific stock index returns

We obtained from Eikon daily open and close prices of the following 10 Asia-Pacific stock indexes: S&P/ASX 200 (Australia), Shanghai Stock Exchange Composite (China), Hang Seng (Hong Kong), TOPIX (Japan), KOSPI 100 (Korea), Kuala Lumpur Composite (Malaysia), S&P/NZX 50 (New Zealand), Philippine Stock Exchange Composite (Philippines), Straits Time Index (Singapore) and Stock Exchange of Thailand Index (Thailand), all of them were denominated in their local currencies to eliminate exchange rate volatility in the empirical analysis. This paper further differentiates between two categories of countries – namely developed and emerging economies, based on Morgan Stanley Capital International’s (MSCI) definition – to conceivably uncover intricate links between monetary policy surprises and foreign stock markets. The first category is formed by Australia, Hong Kong, Japan, New Zealand and Singapore; the rest belongs to the second category. Because all Asia-Pacific markets are closed at the time of ECB announcements, the overnight window (close at day t to open at day t+1) captures the asset prices’ first reaction to monetary policy surprises. We also considered an intradaily window (open to close at day t+1) to pick up any delayed reactions during the next trading day in Asia-Pacific. The returns on a national stock index i corresponding to an ECB announcement at day t is calculated over two time horizons – overnight (R0) and intradaily (R1):

(7) ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[R_0: R_{i,t}^0=ln \frac{p_{i,t+1}^{open}}{p_{i,t+1}^{close}} \]](https://econsilience.ameuglobal.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-445fddd0d719a1925c591f3c97691cda_l3.png)

(8) ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[R_1: R_{i,t}^1=ln \frac{p_{i,t+1}^{close}}{p_{i,t+1}^{open}} \]](https://econsilience.ameuglobal.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-593185be8387772021032bf8ad279a18_l3.png)

where pi,topen and pi,tclose are the opening and closing price of stock index i at day t. They are manually filtered to match each day of ECB announcements during the sample period.

4.3 Controls

We designate STOXX Europe 600 Index as the European stock index (source: Eikon) and compute its intradaily returns to account for potential co-movement with overnight developments in Asia-Pacific stock markets on days of ECB announcements. The choice of horizon is due to the time differences between Europe and Asia-Pacific. Following a common procedure in the literature (Nguyen & Ngo, 2014; Balduzzi et al., 2001), we measured the surprise component of each macroeconomic news i, as the difference between the actual announcement and median forecast obtained from Bloomberg surveys. The discrepancies are then scaled by their respective sample standard deviation such that they are comparable across different indicators. A full list of controlled macroeconomic data releases can be found in the Appendix.

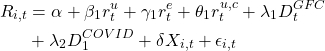

4.4 Proxies

Modelling after Wongswan’s (2009) approach, two proxies are used to measure each Asia-Pacific country’s real linkages with the Euro Area. First, the ratio of each country’s bilateral trade flows (exports plus imports) with the European region to the former’s GDP. Second, the ratio of each country’s exports to its European counterparts to its GDP. They are intended to highlight the European region’s significance as a major trading partner and its propensity to influence the cash flows of foreign companies through its demand for imports. Annual trade data are from IMF’s Direction of Trade Statistics, and annual GDP at constant prices (2010 US$) are from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators database.

Industrial composition of each country’s stock index may also be related to transatlantic linkages (Ehrmann & Fratzscher, 2004). Using data on GICS-based sectoral and total market capitalisation (source: Bloomberg), we proxy the industrial concentration of each country’s equity index in the following areas: a) high-tech, b) business-cycle-sensitive and c) non-business-cycle-sensitive.

See Table 1 for the means of proxies for real economic integration and industrial composition.

5. EMPIRICAL RESULTS

This section reports the estimates of Eqs. (1), (2) and (3) to examine the impact of CMP and UMP surprises on Asia-Pacific stock market performances across different specifications. Where White tests and Breusch-Pagan tests reject the null hypothesis of homoscedasticity, we use White’s robust standard errors that are heteroscedasticity-consistent. The estimated parameters for the control variables will not be widely reported and scrutinised in the remainder of the paper. Generally, the STOXX Europe 600 Index is positive and significant, while the GFC dummy, COVID-19 dummy and macroeconomic announcement surprises (mostly) are insignificant8Results are available on request.. In the regression results of Eqs. (2) and (3), we also reported the p-values from the Wald tests for the equality of coefficients as discussed in Section 3.

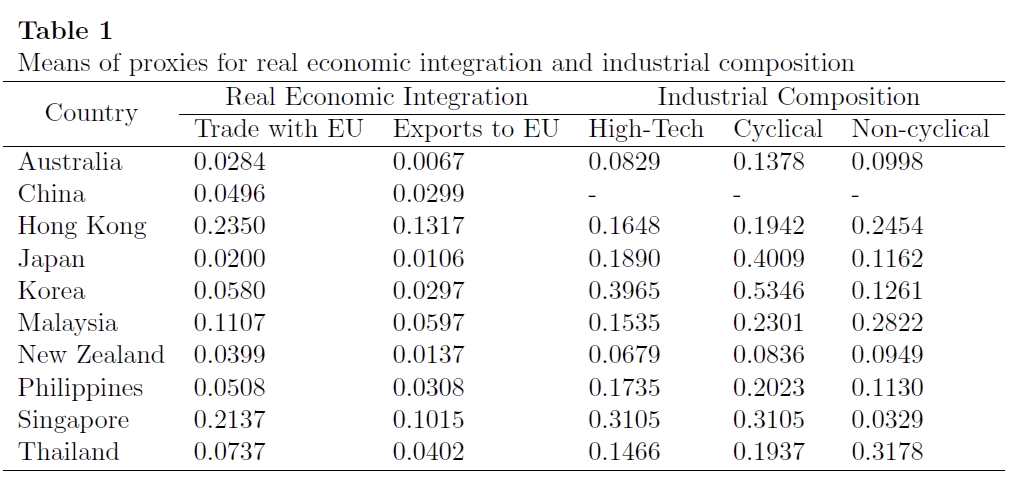

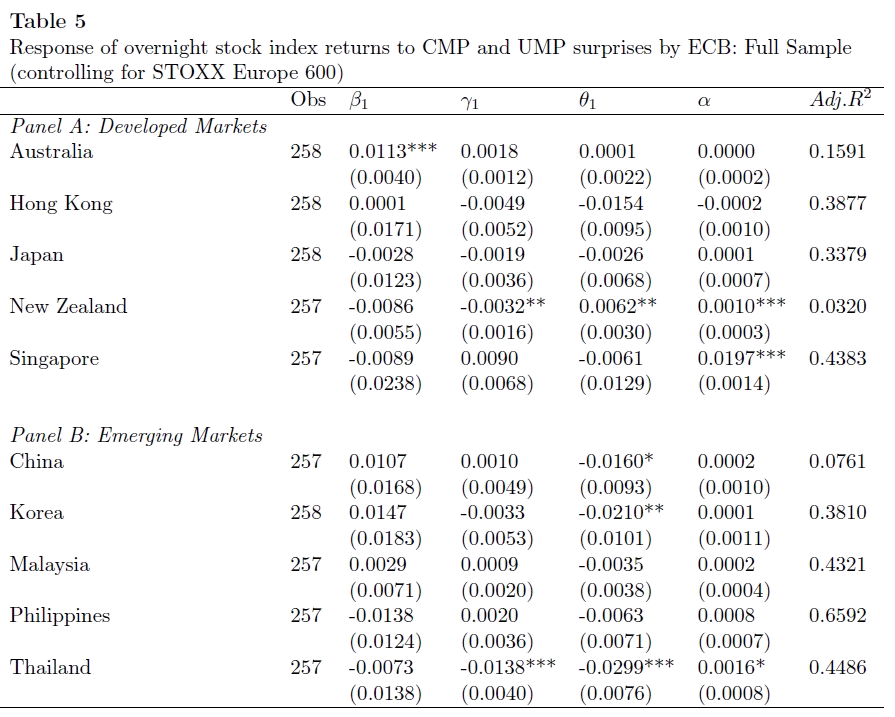

Notes: This table reports OLS estimates of Eq. (1) over ECB announcement dates, regressing overnight (R0) stock returns on the relevant explanatory variables. Euro Area, United States and domestic macroeconomic announcements, the GFC dummy and the COVID-19 dummy are included as control variables. Sample period is January 2001 – January 2021. Obs indicates the number of relevant ECB announcements for each Asia-Pacific country. Panel A includes developed market countries: Australia, Hong Kong, Japan, New Zealand and Singapore. Panel B includes emerging market countries: China, Korea, Malaysia, Philippines and Thailand. Standard errors are below coefficient estimates in parentheses.

*Statistical significance at 10% level

**Statistical significance at 5% level

***Statistical significance at 1% level

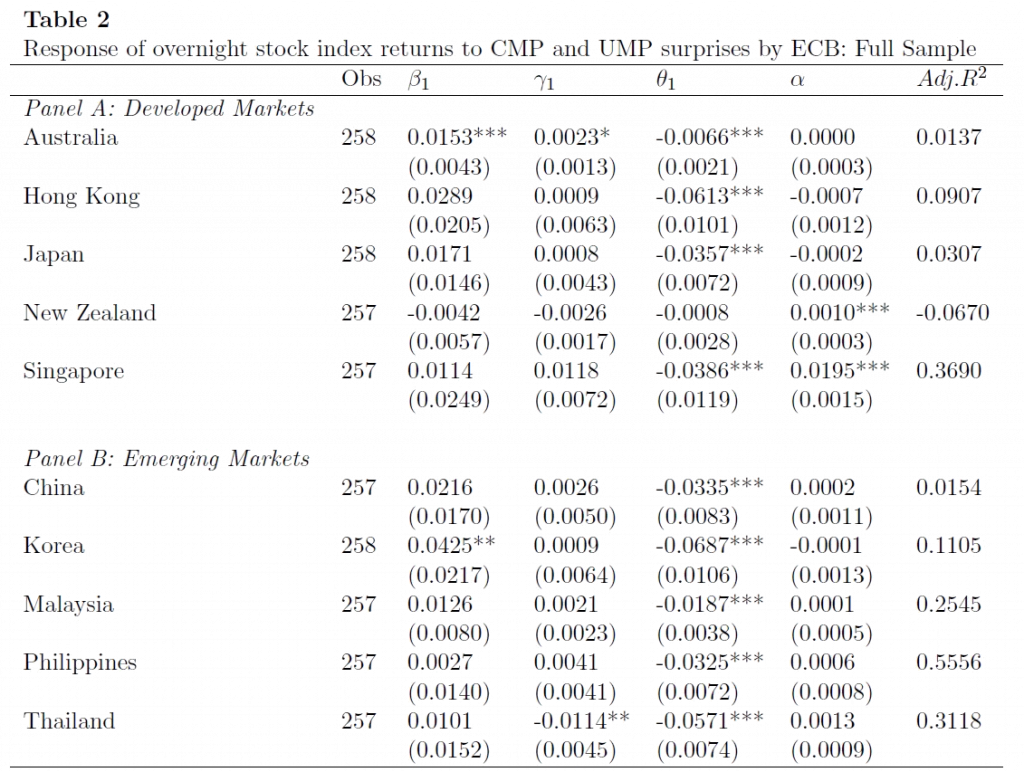

*Statistical significance at 10% level

**Statistical significance at 5% level

***Statistical significance at 1% level

Table 2 and 3 report OLS estimates of Eq. (1) for overnight and intradaily windows, respectively. Panel A and B of each table separately exhibit the responses of Asia-Pacific equity markets based on their market classification. It is evident from Column 3 of Table 2 that most equity indexes do not respond significantly to unanticipated hikes in MRO rate by ECB, except for Australia and Korea. Specifically, a hypothetical surprise 25-basis-point hike in MRO rate is associated with an approximately 0.38%-point and 1.06%-point increase in the S&P/ASX 200 Index and KOSPI 100 Index, respectively. Comparing their corresponding estimated parameters over the intradaily window (Table 3), we provide compelling evidence of rapid incorporation of monetary policy news by both markets since significant coefficients are only observed during R0. We also note that 9 out of 10 stock markets are significantly influenced by UMP surprises by ECB (see Column 5 in Table 2), confirming Fukuda’s (2019) findings. For instance, a monetary policy announcement that caused a 100-basis-point decrease in the Italian-German yield spread (positive UMP surprise) led to an increase in equity indexes, spanning from 0.66%-point (Australia) to 6.87%-point (Hong Kong). While the positivity of estimates (regardless of statistical significance) in Table 2 implies inconsistency with most findings in the literature9The cited papers mostly conclude robust negative relationship between FOMC announcement surprises and returns on Asia-Pacific equity indexes. (Wang & Zhu, 2013; Kim & Nguyen, 2009; Wongswan, 2009) supported hypothesis 1b.

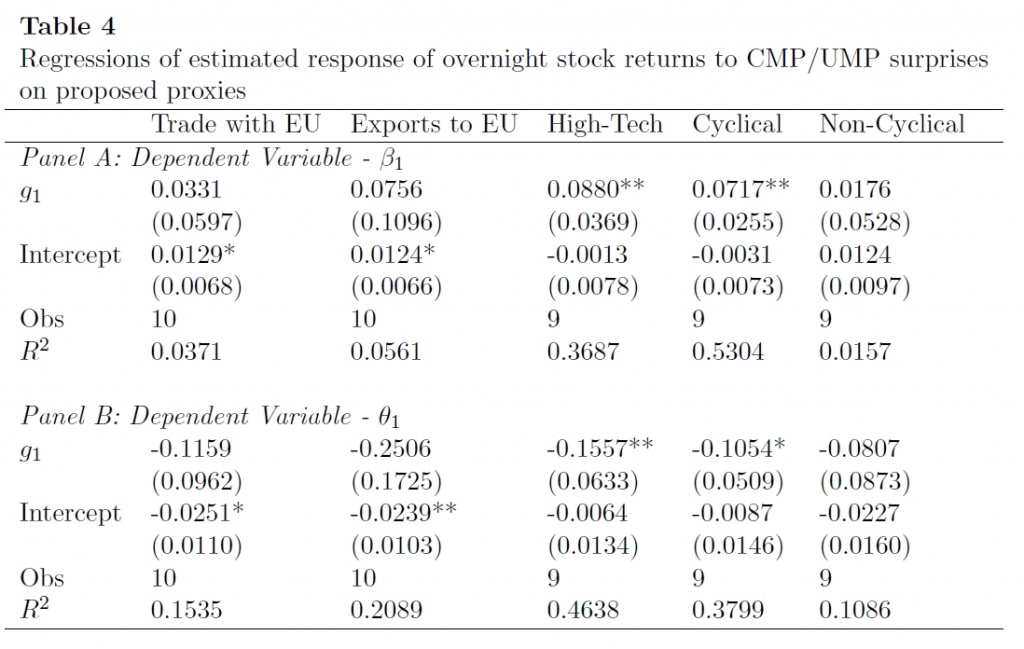

To validate H1b and explore cross-country variation in responses to CMP and UMP surprises, we ran the following and reported the cross-sectional regression results in Table 4:

*Statistical significance at 10% level

**Statistical significance at 5% level

where responsei is β1,i(θ1,i) stock index i’s estimated overnight response to CMP (UMP) surprise by ECB from Table 1, and Zi are proxies for country i’s real economic integration with the Euro area and industrial composition.

Given the small sample in this study (10 Asia-Pacific countries), it is undesirable to simultaneously regress Eq. (9) across all proxies. Columns 2-5 present the estimates of g1, distinguished between Panel A and B based on the choice of dependent variable. While the proxies for real integration do not extend any explanatory power for country-specific heterogeneity in equity price responses (weak evidence for H1b), we can glean additional insights from each country’s industrial composition. In agreement with Wongswan (2009) and Bernanke and Kuttner (2005), countries with high concentration of IT, communication services and consumer discretionary sectors in their equity markets tend to exhibit more pronounced, positive (negative) reactions to CMP (UMP) surprises. This justifies the strong reaction in Korean asset prices from Table 2.

*Statistical significance at 10% level

**Statistical significance at 5% level

***Statistical significance at 1% level

*Statistical significance at 10% level

**Statistical significance at 5% level

***Statistical significance at 1% level

Revisiting the possibility of international stock market co-movement, Table 5 similarly reported OLS estimates of Eq. (1), but with the inclusion of STOXX Europe 600 as an additional control variable. We found that both the significance level and magnitude of overnight stock market responses to monetary policy surprises substantially reduced upon the new variable’s insertion into our specifications, in comparison to the same set of estimated parameters in Table 210The coefficients of the European index are highly significant and positive in all cases. Results are available upon request.. This reinforces the international transmission effects among major stock markets (Hsin, 2004), and echoes Wang and Zhu’s (2013) recent documentation of the role of equity price co-movement in muting the reaction of foreign stock markets to U.S. monetary policy surprises. However, considering the drastic improvement in the adjusted R-squared across all studied countries, we proceeded to control for STOXX Europe 600 when estimating Eqs. (2) and (3).

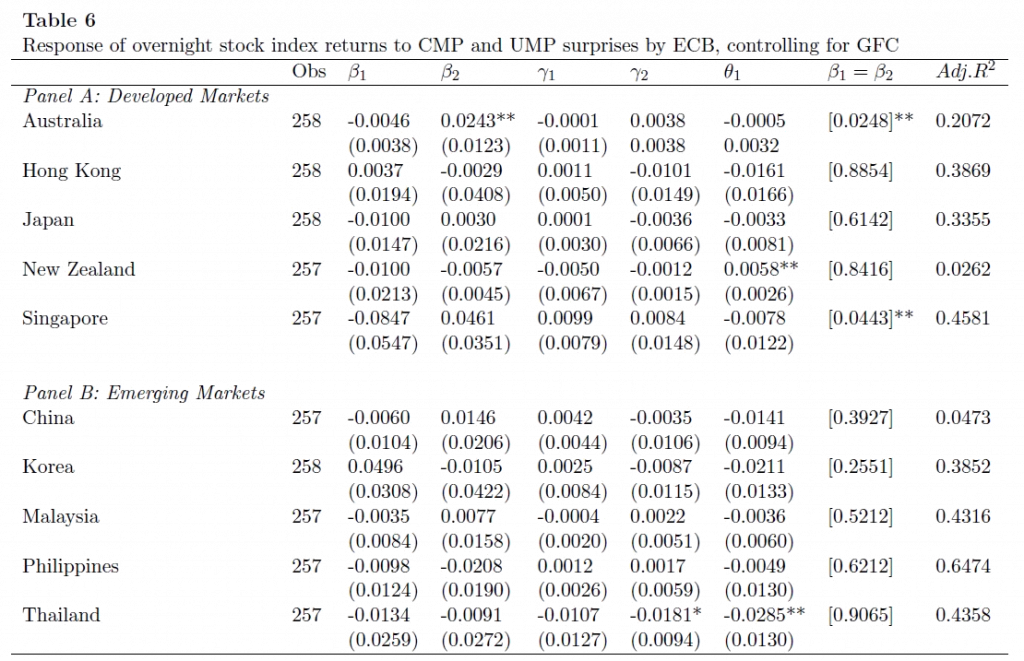

The OLS estimates of Eq. (2) are shown in Table 6. Nearly all estimated parameters are now statistically insignificant – only Australian stock market responded to unanticipated changes in MRO rate during the crisis period, as indicated by β2. Its positivity implies that unexpected monetary easing, in times of crisis, is perceived as a signal of deteriorating economic conditions by stock market investors, therefore driving returns downwards. The Wald tests for equality of coefficients for Australia and Singapore both rejected the null hypothesis at 5% s.l., hence provided limited evidence of a structural change in equity prices’ response to CMP shocks during GFC (Kontonikas et al., 2013).

*Statistical significance at 10% level

**Statistical significance at 5% level

***Statistical significance at 1% level

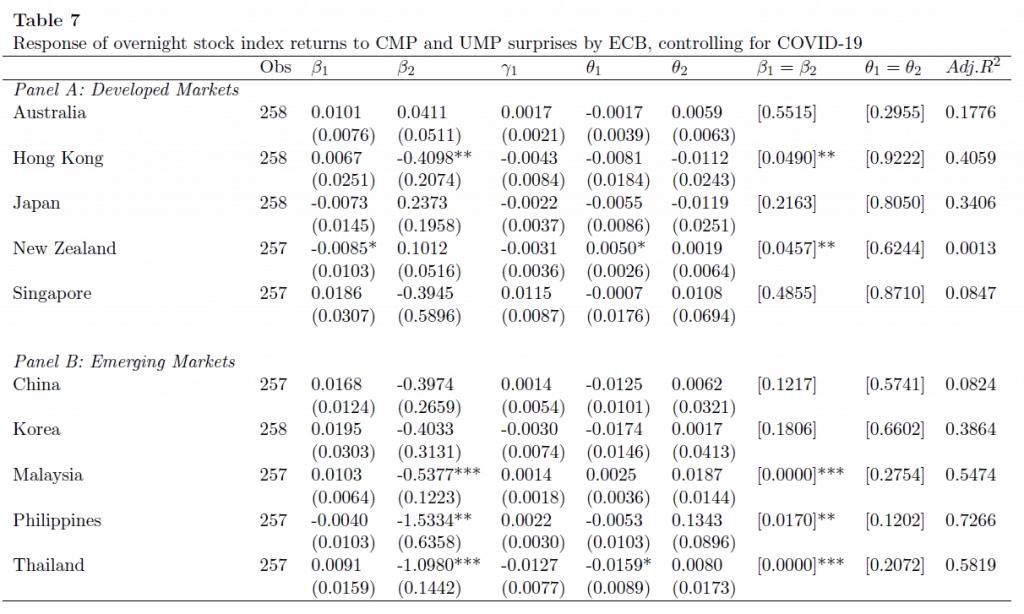

We now turn our attention to investigate yet another potential structural divergence in stock market responses, in view of the ongoing pandemic characterised by strong and frequent policy measures of central banks around the world. Table 7 reports the OLS estimates of Eq. (3). Wald tests for several countries (Hong Kong, New Zealand, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand) suggest a clear structural break between the coefficient estimates for pre-COVID-19 CMP surprises and the ones shortly after the lockdown in Wuhan took place. Interestingly, stock market valuations of these countries are now reacting positively to expansionary shocks in adherence to more conventional wisdom as their β2 estimates have the expected negative sign. Nevertheless, UMP surprises no longer have any meaningful impacts on any of the Asia-Pacific equity indexes.

CONCLUSION

Using an event-study approach, self-built dataset, and high-frequency daily and intradaily data, we extensively documented and discussed the impacts of ECB policy surprises, both conventional and unconventional, on 10 Asia-Pacific stock markets between January 2001 and January 2021. When considering the full sample period, this paper diverges from the findings of most previous studies. It revealed that in response to unexpected rate hikes, most stock markets either displayed statistically insignificant, or positive and significant returns over both overnight and intradaily horizons. UMP surprises, however, have significant impacts on stock performances (when international equity price co-movement were not factored in).

We have provided empirical evidence that country-specific heterogeneity in the magnitude of stock market responses to ECB monetary policy surprises can be attributed to industrial composition but is only scarcely related to proxies of real economic linkages between Euro Area and Asia-Pacific – contrary to initially hypothesised.

Importantly, we highlighted the occurrence of structural shifts across the GFC and COVID-19 episodes, altering equity price reactions to CMP surprises. During the crisis period, stock market investors in some Asia-Pacific countries did not react positively to unexpected monetary policy loosening – this relationship reverted since the onset of COVID-19.

These findings have important implications for policy makers and market participants alike. Decision makers in Asia-Pacific countries may be encouraged to decouple its international financial or economic linkages to shield itself from monetary policy shocks abroad. Meanwhile, financial investors can also revise their trading strategies and risk management decisions accordingly in the event of a proven structural shift in asymmetric stock market behaviours during monetary policy announcements following the COVID-19 pandemic.

A worthwhile extension would be to examine the drivers of these stock market movements through the variance decomposition approach of Campbell and Ammer (1993). Clearly, there also exists alternative asset price-based proxies to isolate CMP and UMP shocks which may be helpful for robustness checks (Chebbi, 2018; Gürkaynak et al., 2007). They are, however, reserved for future research due to data and time constraints.

References

- Balduzzi, P. , Elton, E.J. , Green, T.C. , 2001. Economic news and bond prices: evidence from the US treasury market. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 36 (04), 523–543 .

- Bao, T.H., Mateus, C., 2017. Impact of FOMC Announcement on Stock Price Index in Southeast Asian Countries. China Finance Review 7 (3), 370-386.

- Berge, T.J., Cao, G., 2014. Global effects of U.S. monetary policy: is unconventional policy different? Economic Review, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Q I, 5-31.

- Bernanke, B.S., Blinder, A.S., 1992. The federal funds rate and the channels of monetary transmission. Am. Econ. Rev. 82, 901–921.

- Bernanke, B.S. , Kuttner, K.N. , 2005. What explains the stock market’s reaction to federal reserve policy? J. Finance 60 (3), 1221–1257 .

- Bernoth, K. , Von Hagen, J. , 2004. Euribor futures market: efficiency and the impact of ECB policy announcements. Int. Finance 7 (1), 1–24 .

- Bloomberg.com, 2020. How Unconventional Monetary Policy Turned Conventional (13 September 2020).

- Bohl, M.T. , Siklos, P.L. , Sondermann, D. , 2008. European stock markets and the ECB’s monetary policy surprises. Int. Finance 11 (2), 117–130 .

- Bredin, D. , Hyde, S. , Nitzsche, D. , O’Reilly, G. , 2009. European monetary policy surprises: the aggregate and sectoral stock market response. Int. J. Finance Econ. 14 (2), 156–171 .

- Bulligan, G., & Delle Monache, D., 2018. Financial markets effects of ecb unconventional monetary policy announcements. SSRN Electronic Journal.

- Cahill, M.E. , D’Amico, S. , Li, C. , Sears, J.S. , 2013. Duration Risk versus Local Supply Channel in Treasury Yields: Evidence from the Federal Reserve’s Asset Purchase Announcements Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2013-35. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Washington .

- Campbell, J.Y. , Ammer, J. , 1993. What moves the stock and bond markets? A variance decomposition for long-term asset returns. J. Finance 48 (1), 3–37 .

- Campbell, J.Y., and Cochrane, J., 1999, By force of habit: A consumption-based explanation of aggregate stock market behavior, Journal of Political Economy 107, 205–251.

- Chebbi, T., 2018. What does unconventional monetary policy do to stock markets in the euro area? International Journal of Finance & Economics, 24(1), 391-411.

- Cour-Thimann, P., Winkler, B., 2013. ‘The ECB’s Non-Standard Monetary Policy Measures The Role of Institutional Factors and Financial Structure’, ECB Working Paper 1528.

- De Santis, R. A., 2020. Impact of the asset purchase programme on euro area government bond yields using market news. Economic Modelling, 86, 192-209.

- Ehrmann, M. , Fratzscher, M. , 2004. Taking stock: monetary policy transmission to equity markets. J. Money Credit Bank. 36 (4), 719–737.

- Fatum, R. , Scholnick, B. , 2008. Monetary policy news and exchange rate responses: do only surprises matter? J. Bank. Finance 32, 1076–1086 .

- Fausch, J. , Sigonius M. , 2018. The impact of ECM monetary policy surprises on the German stock market. Econ. Policy 29 (80), 749–799 .

- Fukuda, S., 2019. The Effects of Japan’s Unconventional Monetary Policy on Asian Stock Markets. Policy Research Institute, Ministry of Finance, Japan, Public Policy Review 15 (1).

- Gurkaynak, R. , Sack, B. , Swanson, E. , 2007. Market-based measures of monetary policy expectations. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 25 (2), 201–212 .

- Gürkaynak, R. S., J. H. Wright, 2013, ‘Identification and inference using event studies’, The Manchester School, 81, 48–65.

- Haitsma, R. , Unalmis, D. , de Haan, J. , 2016. The impact of the ECB’s conventional and unconventional monetary policies on stock markets. J. Macroecon. 48, 101–116 .

- Hanson, S. G., Stein, J. C., 2015. Monetary policy and long‐term real rates. Journal of Financial Economics, 115(3), 429–448.

- Hayo, B., Niehof, B., 2011. ‘Identification through Heteroskedasticity in a Multicountry and Multimarket Framework’. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/ abstract=1860827 .

- Hosono, K., Isobe, S., 2014. ‘The Financial Market Impact of Unconventional Monetary Policies in the U.S., the U.K., the Eurozone, and Japan’, PRI Discussion Paper 14A-05.

- Hsin, C, 2004. A multilateral approach to examining the co-movements among major world equity markets. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 13, 433–462.

- Joyce, M.A.S. , Lasaosa, A. , Stevens, I. , Tong, M. , 2011. The financial market impact of quantitative easing in the United Kingdom. Int. J. Central Bank. 7, 113–161 .

- Kim, S.-J. and Nguyen, D.Q.T. , 2009. The spillover effects of target interest rate news from the US Fed and the European central bank on the Asia-Pacific stock markets. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 9, 415-431.

- Kontonikas, A., & Kostakis, A., 2013. On Monetary Policy and Stock Market Anomalies. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 40(7) & (8), 1009-1042. Kontonikas, A. , MacDonald, R. , Saggu, A. , 2013. Stock market reaction to FED funds rate surprises: state dependence and the financial crisis. J. Bank. Finance 37 (11), 4025–4037

- Krueger, J.T., Kuttner, K.N., 1996. The Fed funds futures rate as a predictor of Federal Reserve policy. J. Futures Markets 16, 865–879

- Kurov, A., 2010. Investor sentiment and the stock market’s reaction to monetary policy. Journal of Banking and Finance 34 (1) 139–149.

- Kuttner, K.N. , 2001. Monetary policy surprises and interest rates: evidence from the fed funds futures market. J. Monet. Econ. 47 (3), 523–544 .

- Patelis, A.D. , 1997. Stock return predictability and the role of monetary policy. J. Finance 52 (5), 1951–1972 .

- Nguyen, T. , Ngo, C. , 2014. Impacts of the US macroeconomic news on Asian stock markets. Journal of Risk Finance 15(2), 149-179.

- Rigobon, R. , Sack, B. , 2004. The impact of monetary policy on asset prices. J. Monet. Econ. 51, 1553–1575 .

- Rogers, J.H. , Scotti, C. , Wright, J.H. , 2014. Evaluating asset-market effects of unconventional monetary policy: a multi-country review. Econ. Policy 29 (80), 749–799 .

- Tillmann, P., 2016. Unconventional monetary policy and the spillovers to emerging markets. Journal of International Money and Finance 66, 136-156.

- Wang, J. , Zhu, X. , 2013. The reaction of international stock markets to federal reserve policy. Financ. Markets Portf. Manage. 27 (1), 1–30 .

- Wang, S. , Mayes, D.G. , 2012. Monetary policy announcements and stock reactions: an international comparison. N. Am. J. Econ. Finance 23 (2), 145–164 .

- Wongswan, J., 2006. Transmission of information across international equity markets. The Review of Financial Studies 9, 1157–1189.

- Wongswan, J., 2009. The response of global equity indices to U.S. monetary policy announcements. Journal of International Money and Finance, in press.